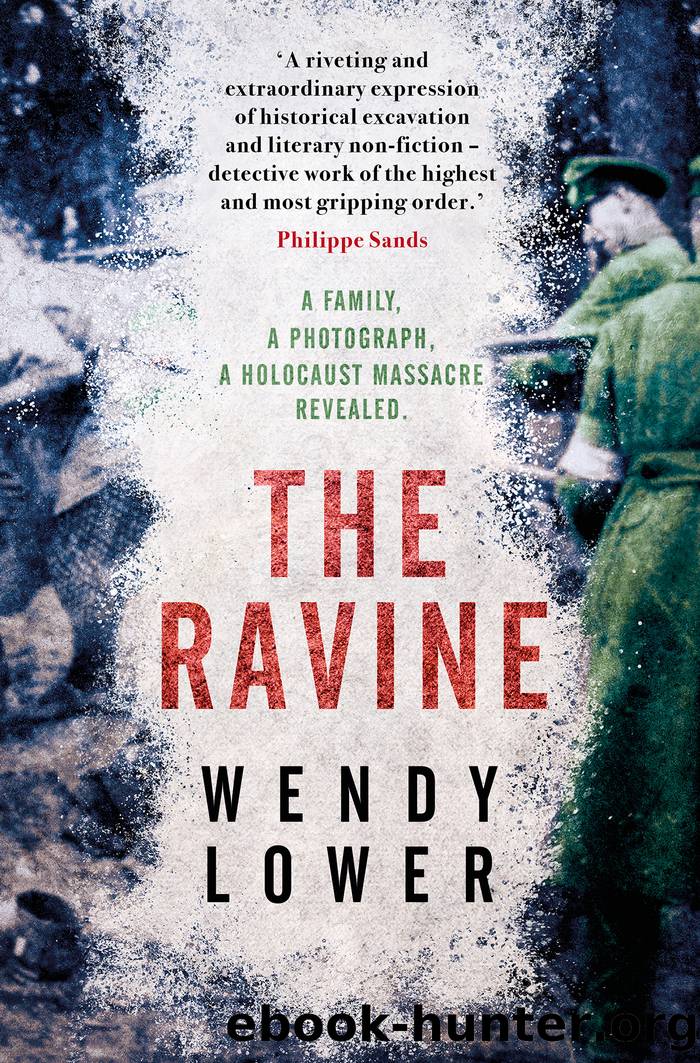

The Ravine by Wendy Lower

Author:Wendy Lower [Lower, Wendy]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781800246669

Publisher: Head of Zeus

7

THE MISSING MISSING

PHOTOGRAPHS DOCUMENT AND recall the past; they depict what is now gone, and they conjure up emotions. Survivors retelling their life stories on film hold up personal photographs at the end of an interview. They cling to the photographs because they often are all they have of loved ones who were disappeared or killed without a proper burial and without a formal death certificate documenting their existence. When I researched photographs as an element of the Shoah Foundation testimonies (searching more than fifty thousand videotaped survivors), I discovered a pattern. Survivors presented snapshots of wartime atrocities as well as family photographs, exhorting viewers to look at the atrocity shots, declaring, âThis is what happened to my family, and to Jews across Europe.â Survivors, in this way, beseech us to remember. Their identification as victims starts with their family history of persecution and the experiences of loved ones who were unable to emigrate from Europe and whose exact fates remain unknown. We know what happened to the family in the Miropol photograph, yet they are among half a million unidentified Holocaust victims in Ukraine.

World War II introduced a new understanding of the depths of human cruelty in the massive crime of genocide; this era also opened up a new chapter in international humanitarian relief and rehabilitation programs, aimed mostly at assisting refugees, searching for the missing, and reuniting families. Millions of civilians and prisoners of war in Europe had been forcibly relocated and detained in tens of thousands of sites run by the Nazis and their allies: concentration camps, labor camps, ghettos, and killing centers. The uprooted in Europe included hundreds of thousands of orphaned children. At warâs end, the Allies implemented the Yalta Agreement to repatriate displaced persons (DPs) to their countries of origin. The Allies took on the enormous challenge of caring for âstatelessâ Jews and orphans who had no home to return to; to house them they used available sites such as the former concentration camp Ebensee, a twelfth-century monastery near Dachau, or Feldafing, a former Hitler Youth Camp in Bavaria. The Jews among the displaced persons, numbering about 250,000, called themselves by the Yiddish or Hebrew term for âremnant,â oysgevortzlte, âa person ripped from his roots,â or di nisht dershtokhene, di nisht gehargete, di nisht gekoylete: âthe not killed, the not slain, the not gunned down.â The term survivor came later. In the immediate aftermath of the war, Jews said, âI am what is left,â not, triumphantly, âI am a survivor.â The novelist Meyer Levin recalled in his autobiography, In Search, that traumatized Jews who appeared in the European offices of Jewish relief agencies presented a fragmented account of what had happened, using words and locations, such as Treblinka, that he had never heard of. As Levin described it, these Jews all had their own mental snapshots, which in 1945 could not be âproperly developed.â

A ragged sixteen-year-old Ludmilla Blekhman returned to liberated Miropol on June 30, 1944. She wore the shirt that she swore had saved her.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Room 212 by Kate Stewart(5106)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4810)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(4773)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(4351)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4206)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4104)

Killing England by Bill O'Reilly(3998)

Say Nothing by Patrick Radden Keefe(3976)

I'll Give You the Sun by Jandy Nelson(3431)

Shadow of Night by Deborah Harkness(3361)

Hitler's Monsters by Eric Kurlander(3331)

Mary, Queen of Scots, and the Murder of Lord Darnley by Alison Weir(3208)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(3199)

Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell(3156)

Darkest Hour by Anthony McCarten(3121)

Margaret Thatcher: The Autobiography by Thatcher Margaret(3081)

Book of Life by Deborah Harkness(2935)

Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine by Anne Applebaum(2930)

The One Memory of Flora Banks by Emily Barr(2857)